|

How does one imagine the new, or is it a vision that comes to a mind that is neither projecting itself nor meekly following another? Is there an intent that we are born with? These were questions that came up often during the Mahabharata Immersion. So it came as no surprise to us when the last group came up with an innovative possibility. They were exploring arjuna, and started the process with a very new idea: kunti goes to karNa and tells him of his birth, begs his forgiveness and seeks his generosity, “spare my children, your brothers” she asks. In our exploration, karNA says “I will first have a conversation with arjuna and draupadi”

What did it take for kunti to finally own up her abandoned son? Did she think of him ever? What is he intention? Is it to stop the war or secure victory for the sons she has always owned up? None of these questions could be explored or answered. The actors who attempted to step over the threshold of the known were quickly pulled back to the unresolved and unbearable hurts of the past. karNa seeks a restoration not of his status but of self that has called out in despair for some one to affirm it and honour it. The child of soorya has remained in the shadows for all his life. No compensation can suffice. His pain is unbearable now that he knows who he is. karNa is unable to let a new conversation begin. arjuna tries to envision a new possibility, but karNa is deaf to it, and soon recriminations and counter recriminations fly unhindered! “I have to let go all my cherished ideas about myself, my world view as much as you have to step outside of your refuge” arjuna begins. draupadi adds her bit, “I too must look at you without the hate I have held for you” she adds. But the air is soon poisoned by the demands for the impossible, a turn back of the years, a drawing out of the pain of discrimination and denial. The group was completely stunned as were the actors. The deeply buried hurts and years of repressed yearning to be seen and affirmed and appreciated came bursting forth. The ‘old’ was insistent in its demand that its residues must be attended to, the unresolved must be acknowledged and the disowned must be embraced. One of the protagonists who works with the problem of trafficking and prostitution shared his context, how incredibly difficult it is to help the women scared by years of abuse to let go of the old identity. Neither her family nor the community will really create a new space, nor can she look at herself without her own judgement (internalized from society no doubt). The trishanku swargam of the kota with its own unique culture of celebrations and compensations seemed a better world. karNa finally preferred the love of duryOdhana to the possibility of an ending of the war and the beginning of a new life as the eldest pAndava! As India tries to come to grips with its greatest affliction namely discrimination based on birth, can we look at this insight. The dalit who has been wounded by stigma has to be acknowledged and embraced as a human being with grace and dignity. Reservations and conversions to another religion do not wipe away her tears, they do not alter the psyche and make it whole. The ‘failure’ of the last group to find a new conversation was a huge eye opener for us. So we come to karNa! The group chose to examine karNa through the encounter he has with his father soorya and the subsequent encounter with indra disguised as a poor brahmana. Being owned up by the father is a shock. It offers an opportunity to karNa to step out of the constructs which he has created for himself: one of a sootaputra stigmatized and victimized for something beyond his control, and the other of being the epitome of generosity, the kodaivallal, and the third as duryOdhana’s friend, eternally grateful for the gift of angada desham. As the actors entered these characters and struggled within, all of us were deeply touched by the poignancy of the situation. karNa could not step out of the one self construct that was truly of his making, the generosity personified. He gives away his kavacha and kundala, he cannot say no to indra! karNa is a favourite among us Indians. Late Prof. Pulin K Garg (IIM A) used to say that the central issue for understanding the Indian psyche is to understand the nature and dynamics of denial, discrimination and deprivation. karNa is the arch archetype of all three converging in one person. karNa has always known that he was worthy deep down in the recesses of his heart, but he was reminded of his unworthiness as a stigma of birth. The compensation he received from duryOdhana who made him the angada raja was after all a proxy identity that only reinforced the denial, discrimination and deprivation. The desperate struggle to come to terms with a fresh new possibility, of being affirmed at a very deep level, a secret that karNa held to himself was too scary. karNa held on to the one construct he had built, his bulwark of affirmation that he was worthy, one that he had acquired through his greatness of spirit. All the group reflections centered around these aspects. How deeply each of us seek affirmation of our being, and how profound and secret are the wounds that we retain when this is not forth coming? And yet we know in our hearts the gifts we are born with. Perhaps the courage needed to affirm ourselves as we know we are and assert our being from that foundation is several times more than the effort required to hang on to compensations and proxy affirmations, how ever painful this effort may be.

1 Comment

We present ourselves to the world through masks. The persona that we call the ‘actor’ is the mask, and this mask is energized by the other personas namely the victim, the guardian, the judge, the beckoner, the fiend and the dreamer. The rasa anubhava is closely linked with what is energized/ triggered. The exploration of the mask was disturbing. We are often unaware of the fact that we are presenting a mask, it is when we start drawing what is really the face inside the mask that we start to realize the connection! In presenting ourselves the way we do, we also reinforce our constructed self, and therefore clog our senses. We cannot hear, see, smell, taste or touch the emerging new reality.

So we come to karNa! The group chose to examine karNa through the encounter he has with his father soorya and the subsequent encounter with indra disguised as a poor brahmana. Being owned up by the father is a shock. It offers an opportunity to karNa to step out of the constructs which he has created for himself: one of a sootaputra stigmatized and victimized for something beyond his control, and the other of being the epitome of generosity, the kodaivallal, and the third as duryOdhana’s friend, eternally grateful for the gift of angada desham. As the actors entered these characters and struggled within, all of us were deeply touched by the poignancy of the situation. karNa could not step out of the one self construct that was truly of his making, the generosity personified. He gives away his kavacha and kundala, he cannot say no to indra! karNa is a favourite among us Indians. Late Prof. Pulin K Garg (IIM A) used to say that the central issue for understanding the Indian psyche is to understand the nature and dynamics of denial, discrimination and deprivation. karNa is the arch archetype of all three converging in one person. karNa has always known that he was worthy deep down in the recesses of his heart, but he was reminded of his unworthiness as a stigma of birth. The compensation he received from duryOdhana who made him the angada raja was after all a proxy identity that only reinforced the denial, discrimination and deprivation. The desperate struggle to come to terms with a fresh new possibility, of being affirmed at a very deep level, a secret that karNa held to himself was too scary. karNa held on to the one construct he had built, his bulwark of affirmation that he was worthy, one that he had acquired through his greatness of spirit. All the group reflections centered around these aspects. How deeply each of us seek affirmation of our being, and how profound and secret are the wounds that we retain when this is not forth coming? And yet we know in our hearts the gifts we are born with. Perhaps the courage needed to affirm ourselves as we know we are and assert our being from that foundation is several times more than the effort required to hang on to compensations and proxy affirmations, how ever painful this effort may be. Our identities are created through an engagement with our world. They are not rigid and hard entities. The mahabhArata is a tale of destruction that ensues when people in power rigidify their identity. One can only feel threatened by reality as it emerges since the ever changing world will only sometimes conform to our needs and expectations of it! One must then defend ones identity with violence and seek to dominate the world and make it conform to our formulation.

One of the explorations that the Immersion offered was the process by which we form our inner selves. We can engage with the world from a fullness within, and when the world welcomes this expression there is an unfolding and love. It can choose to negate the offering and one feels hurt and challenged. Coversely, one can withdraw from all engagement and feel depleted within. The world in its turn could choose to ignore us, and leave us to our own devices in our lonely world. The world can choose to accept our depleted state and offer help. These experiences keep changing but we tend to hold on to one or the other of these experiences as a defining state and build our identities around this assumption. The idea behind asking groups to choose a character they wish to explore and making them explore the whole context that is created equally by the various protagonists is based on this understanding of how one creates dukha by getting entrenched in a few possible ways of being and by holding the others in fear. Shakuni is universally considered to be a villain. The group that chose to explore shakuni ‘inside out’ took a difficult path. It came as no surprise when the group decided to have two people playing each of the three roles namely, shakuni, yudhishtra and duryOdhana! The idea of exploring villainy is daunting. The scene they explored was the one where yudhishtra is enticed to gamble. Yudhishtra struggles with his shadow self. The presentation of always being righteous and playing by the book has been achieved by repressing a part of the self that would like to throw caution to the winds is challenged. yudhishtra has the freedom to say no, but his compulsion gets the better of him. shakuni is an honest broker, he is here to ensure that his sister and her family is not cheated by the scheming kuru clan. When the standard of honour and integrity expected of a great Kingdom is not lived up to, one has to fall back on ones ingenuity. The enactment centered around the encounter between a shakuni employing his wits to survive and proper in a space where there is no real respect for the law, and the law abiding yudhistra battling his own inner demons. The new perspective that was presented gripped the group: shakuni was doing what any one who has seen his sister being illtrated by the in-laws would do! If we remove the idealized picture of world, we see its underbelly, a chaotic place where each one is trying to defend them selves, to survive and hopefully come out on top! In such a world, the trickster’s wits are essential. In all ancient mythologies it is the trickster hero who gets the fire from the gods, and who helps the tribe grow without paying a heavy price. Seen this way, krishNa is a trickster too! The heavy price paid by a socialized mind also became evident. yudhishtra is the arch symbol of the “good son/ good citizen” the price of being called good, of having to control ones impulses and postpone its fulfillment is hidden craving for the forbidden. Also, the group got in touch with the helplessness that assails us when the world around us is not law abiding, and we value honesty. Along with the control we exercise over our impulses, we give up our intuition and animal sensing of danger and of the other persons motives. What happens to us as a nation when the context becomes unpredictable and the rule of law does not operate? We tend to get paralyzed or we fall back on our own resources of power and cunning. The chaos that ensues also releases some of our constraints and our shadow sides play up. A negative spiral starts ending up with a raw use of power, there is fighting and war! We see this in families too. What of dritarAshtra?

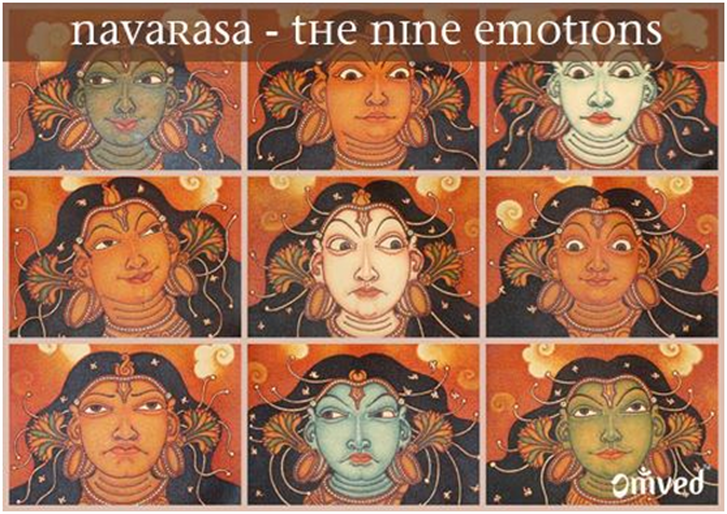

The scene the group sought to explore was the one where duryOdhana insists upon vidura taking the letter of invitation to the game of dice to yudhishtra. gAndhAri was the fourth protagonist. A petulant duryOdhana demands that his father do his bidding. dhritarAshtra demures, and gAndhAri takes the side of duryOdhana. She holds dhitarAshtra ransom to her sacrifice and her having felt cheated. duryOdhana emboldened by his mothers indulgence and as blind to her motives as she is to reality, rants about his entitlement. vidura is called, and his sane argument is dismissed out of hand, he is reminded of his illegitimacy and his dependency and finds no answer to the belligerence of duryOdhana. dhritarAshtra is tried to enter his dharma sankata deeply and establish his space as the creative possibility. What struck the players and the group was the various types of indulgences that each of these archetypes represent. duryOdhana is entrenched in his sense of entitlement, no argument about what is just or what is deserving will penetrate his deafness to all but his obsessive desires. Wise vidura the anchor to the dharma sankata in dritarAshtra’s mind gives up his polarity, he cannot confront the challenge of gAndhAri as she insists on compensating for her own self inflicted deprivation by indulging her son. Is she also hitting back at her husband, showing up his inadequacies and telling him that being a father who acquires power for his son is the only legitimate role, that all of dritarAshtra’s arguments as a just king are invalid. His articulation of the dharma sankata is weak, almost an apology, and he is easily persuaded to give in to the tantrums of his son and wife that to act from the role of a king; a role that impacts the entire kingdom and not just his little family. The first set of reflections that came from the group were around the role of gAndhAri. Why did she choose to blind herself? Was it not important for her to make up for her husbands incapacity and form a strong team? The role of a wife and a mother in creating a context that is nurturing and at the same time dharmic and disciplined became a point of enquiry. Also, the power of a child who demands impulsively became apparent. The will and the clarity that it takes of a parent to draw meaningful boundaries, and how important it is in helping the child mature, were examined in great detail. duryOdhana was seen as a monster created by the two parents- blind to everything except their own shattered dreams. duryOdhana was a proxy through which the father was living out his dream of being an uncontested king, and the mother of being a person who could assert her capabilities and stand her ground. The tyranny of the idea of entitlement then took up the attention of the group. Are we like King Canute who tried to order the waves of the sea to obey him? And when the world pays scant regard to our dreams what do we do? The most common recourse seems to be of self-defeat and glorifying our loss through self-inflicted hurt. The other reaction seems to be to insist upon the fulfillment of our wishes by hook or by crook. Reordering our idea of the world and its ways, and finding a resilience within through which to find an honorable way of engaging with the emergent reality seems very difficult. The weakness of vidura triggered a whole set of reflections. We often know what is right and just, we make some gestures to satisfy ourselves that we tried to influence the outcome, but stop when a real price has to be paid. How does this impact our society and our nation? Are we looking for a ‘strong and wise leader’ behind whom we can protect ourselves? As soon as he/ she does not give us what we want (based upon our own narrow and self centered perspective) do we bring him/ her down by walking away? Aquiesing? ……is democracy another name for demanding an indulgence towards our ill-considered demands? How do we uphold the fairness (nyAya) towards the whole before we take for ourselves? The discussion then veered towards the global impacts that are the outcome of each of our indulgences, our need to consume, needs that are often not necessities, needs triggered by advertising that appeals to our vanity or our lust. The factories around the world do not produce green house impacts because they are unaware, they do so because we demand that our needs be satisfied and they make healthy(!) profits through supplying the good we demand (not by questioning if we really need them). Unhealthy foods do not proliferate because the fast food companies cheat us, it is because we cannot manage our appetites and the pull of taste overrides the knowledge of health impacts. The dritarAshtra, gAndhAri duryOdhana combine is devastating the world. Yogacharya Krishnamacharya once said that the mark of a healthy person is the ability to feel the nava rasas deeply and appropriately, and then return to shAntam the moment the context has passed. We explored this through techniques used in traditional theatre. This exploration threw up a lot of introspection in the group.

The group then proceeded to take up a few of the characters that they wanted to explore further. These explorations were done in the following manner: one of the participants announced that they would like to explore X character, others who wanted to join in volunteered. We ended up with 5 groups namely, duryOdhana, shakuni, dritarAshtra, karNa and arjuna. The group was supposed to enact a key scene, and the person who was the anchor took up other characters in the first two rounds of the enactment, and then became the character they chose. In the third round, the exploration of a new and different way of response was expected from the central character, and therefore from the others too as the new possibility developed. Let us see what came of the duryOdhana exploration. The group wanted to explore the scene where duryOdhana comes to the palace of illusions, wets his dhoti and is laughed at by draupadi. What was extraordinary to start with was that 3 of the six that formed the group were women and the anchor was a woman! What a courageous step to take, to say let me get into the skin of an archetype that torments women! The central exploration was around the impossibility of duryOdhana to take a joke. Here is a very talented and powerful young man who is so caught up with his narcissism and child mind that he cannot bear to be found making a mistake. “I must be seen and appreciated in the way I want to be, and in no other way!” he screams. “I cannot be seen as small and inadequate, if I am I will be so vindictive that I will plot your humiliation.” “This or nothing, all or none, now or never” the discourse of a five year old narcissus believing that he is the king of all he surveys. The hurt of being seen as a fool by the woman he most admires. The power of envy came through- “they possess that which is the most desirable” and compounded by narcissism, this becomes a reminder of ones own lack of worth. A new alternative, one where duryOdhana can laugh at himself simply did not take off!! The women found immense release in seeing how small and wounded the psyche of duryOdhana was. The men confronted the prison that duryOdhana lives in when he is constantly seeking affirmation of his worth. At the end of the enactment the whole group reflected upon and voiced the duryOdhana, draupadi and karNa (the main protoganists). The innocence and playfulness of draupadhi surprised by the vehemence of the insult felt by duryOdhana, karNa’s proxyhood and blind empathy with his friend, and the depth of hurts that each of carry from our early child hood came through clearly. The totally unrealistic conceptions of self and the world that a child has as he/ she awakens to their own self conscious existence became clear. This is the root of Avidya. Hurt to our own construct of our selves is inevitable, and as a part of that, the let down of the world (that we have imagined) is also inevitable. However, a large part of our victim selves carries these hurts, hugs them close and makes a promise never to be hurt again! The rest of ones life is a mortgage to this promise. Any act of vengefulness that is triggered by this mortgage is seen as a just recompense. How extraordinarily wasteful of ones own life and how we hold others around us hostage to our victimhood! Many family feuds and community antagonism seem like reflections of the duryOdhana child mind. India Vs Pakistan? Immature patriotism? Ill-conceived nationalism?..... Madam Blavatsky says in the Secret Doctrine, “…All this is very puzzling, to one who is unable to read and understand the Purana-s, except in their dead letter sense. Yet this sense, if once mastered, will turn out to be the secure casket which holds the keys to the secret wisdom. True, a casket so profusely ornamented that its fancy work hides and conceals entirely any spring for opening it, and thus makes the unintuitional believe it has not and cannot have any opening at all. Still the keys are there, deeply buried, yet ever present to him who searches for them”.

How does one discover this key that opens up the secure casket? The mere retelling of the stories and the aesthetic appreciation of its portrayal through dance and art is not enough. Recently a group of 32 people undertook a search to find the key, a search within because surely the key is not lying on the ground somewhere! We set out to explore the meaning of the word puraNa: pura api navam meaning ancient yet nascent. How does an ancient story become nascent? It does when it lives in the moment through us. So we set out to share our exploration of the ways in which each of the heroes of the mahabhArata lives in us, and through us; how these archetypes arise in various contexts and relationships. We became the subjects and the objects of our enquiry, we agreed to disclose the turmoil and struggle of our lives, the dilemmas we face that get reflected in the many stories of the mahabharAta. We dug deep into ourselves and watched the drama unfold as the daivic and asuric forces within us played out their eternal mantan; six days of intense self-enquiry, self-disclosure and sharing threw up a lot of insights. It was a watershed event for me to facilitate the group and watch the space unfold with vibrancy and meaning. We used therukkoothu, inner work, drawing, dialogue, sharing and enactment to dive deep into our psyche. It must be emphasized that a laboratory learning space is one where there is very little discourse or interpretation. The participants explore their own self, in their own context based on the triggers provided by the group exploration into the mahabhArata. The facilitator enable a deep and intense exploration where catharsis and ‘acting out’ of long held parts of the self become safe and infact become the most important starting points of introspection. Through exploring the metaphor of the mantan we discovered that the willingness to watch the flow of energy between the dark and light sides of our psyche is an essential pre-requisite. The moment we judge the dark as bad we bring in our socialized and conditioned thought into the process, the mantan stops. The “good” is elevated; the “bad” is demonized and repressed. The possibility of looking at the two as forms of energy, of befriending ones own violence and thus understanding its structure and nature is lost. The possibility of looking at our hurts and staying with them so that they do not trigger processes of defensiveness and aggression is lost. The possibility of ending the poison that is generated within our psyche, and discovering aishwarya is lost. Is that why there was the mahabhArata war? We explored many turning points in the saga of the pAndava and the kaurava. At each such turning point, the archetypal human energies are clearly etched out, the outer dilemma and the inner cacophony can be explored, ones own inability to end the ancient war with the “other” and find a space for the emerging vulnerable and fresh life can be confronted. We explored the archetype of draupadi through a dialogue with Jyotsana Narayanan (an acomplished dancer and dance teacher from Kalakshetra). She shared with us her exploration of pAnchAli (as she likes to call draupadi). Through the day we had explored the various personas that make up our psyche, namely the actor who is like a vessel endowed with many capabilities, the victim who holds hurt and pain, the guardian who is vigilant and ready to fight the world, the judge who evaluates us based on societal rules, the beckoner who searches for escapes, the friend who holds affection and honest appreciation, the dreamer who is the receptacle of our destiny, and the meditator who remains in silent and profound awareness of every nuance of our inner space. Jyotsana talked about the immense shakti of pAnchAli as she faces the court and asks each one of her husbands why they are frozen, confronts bheeshma with his praralysis and challenges the kauravas from a core of integrity. When every effort to awaken the noble and the compassionate yield no outcome pAnchAli awakens to her divine potential. pAnchAli becomes pure aspiration for the Thou, she lets go of all effort sourced in the self, accepts her vulnerability and discovers krishNa, the Thou within. Every one of us was stirred and touched by the dialogue. The idea that pAnchAli was a victim gave way to the realization that it was the vulnerable and the pure spark of atman, born of the sacred fire, a gift from the divine, the purest dream for oneself. When one awakens to this vulnerable self, the mantan begins. Perhaps in this insight into the possibility of pAnchAli lies a window for each of us. Could we end our love affair with our victimhood and the vengefulness that it unleashes and open ourselves to embracing our vulnerability? In that baby step there lies an immense possibility for all of us. I came into the study of Yoga at a time when I was searching for a direction in life, a meaning that was meaningful and inspiring. I was just out of college, very concerned about issues like Environmental Degradation; I had read “Limits to Growth” and was having intense conversations with my friends on Marx and Marcuse. We met a lot of the early 60’s generation of ‘conscientious objectors’ people who would later on be called Hippies, and who would be called the Woodstock generation.

I was very fortunate in that I spent a decade learning inner work from Pulin K Garg and Yoga from Krishnamacharya simultaneously. The Yoga Sutra provided a daily practice and an intellectual rigour, it led me into the world of meditation and contemplation. Process work opened up internal spaces, helped to heal deep wounds and reclaim my emotional self. I have gone on to base all my work with individuals and organizations on these two pillars of my learning. However, I have been deeply concerned with the way in which Yoga is taught today and inner work is offered. I was thrilled when a few years back a group of young seekers in their thirties approached me with questions that were exactly the ones I had asked my self at a similar age. Not that I have found the answers, but I have grooved the questions. They were explicitly seeking a way of enquiring into these life questions through Yoga. We have spent a couple of years on this “collective contemplative conversation”. We studied the Yoga Sutras in an experiential way. The group was ready for some experimentation so I dusted up my Rorshach Kit (I had learnt to use it from Pulin), and did what Pulin and I had wanted to do a long time ago: use the insights from Rorschach to design a meditative practice. The group has stayed with the enquiry for more that two years, experienced profound transformation and made clear choices in discovering alternative ways of living. The group has formalized itself, it is called Ritambhara, (www.ritambhara.org.in) and the members see themselves as “spiritual activists”, my wife Sashi and I are Mentors for the group. I was thrilled when I got this mail from Sangeetha Sriram. It has given me the adhikaar to offer life coaching based on the Yoga Sutra. After a long weary journey, I was led on to the doorstep of Yoga. Being and learning with our teachers Raghu Ananthanarayanan and Sashikala Ananth and fellow-seekers in the community Anita Balasubramanian Rajeev Natarajan Priya Nagesh Naveen Kumar V Radhika Rammohan Saraswathi Vasudevan Rengarajan LV Parthasarathy Ramanujam Kokilashree AlangaramGowtham Sandhya Anju Sandhya Manian for three years now has been a very rich experience. Here is one articulation of the way I see the personal and the collective; how everything (climate change, my eczema, patriarchy, genocide, my breath, my incessant mind) comes together in One Vision. Sangeeta Sriram ******* 1.The Journey My Journey I begin by seeing and acknowledging that I'm on a journey, and that my limited mind / my small self is incapable of understanding and undertaking it all by 'itself'. I need help. Patanjali's invitation in the form of the First Sutra says 'Aaah! Now you're ready!!' atha yogAnushAsanam. This is the point I gain the ability to look at the 'Hero's Journey'. I am disillusioned enough to start asking the questions: - What is my journey towards? - Where am I in the journey? - How did I get here? - What lies ahead? Bringing awareness into 'Who I am' not in a philosophical but an absolutely practical way: my personality, tendencies, gifts, questions, aspirations, meaning-making, fears, explorations, experience, learnings, challenges, relationships, behavioral patterns, attractions, aversions, etc. In other words, I begin to intuitively understand my 'Universe', along with which naturally, but slowly, unfold 'self-acceptance' and 'compassion to the self'. This understanding becomes the seed of true non-violence / ahimsa. Others' Journeys As a consequence of my beginning to understand / have insights into my own journey, I begin to see and acknowledge, begin to understand / have insights into others' journeys. As I start bringing awareness into my universe, I start bringing awareness into others' Universes, along with which naturally unfold 'acceptance of others' and 'compassion to others', little by little. Though my sense of discernment / judgement sharpens, I experience myself as less and less 'judgemental'. The seed of ahimsa has begun to sprout. The Collective Journey A pattern / an understanding emerges: It is one of an upward spiral movement that the Consciousness is undertaking. Suddenly, the world that seemed all chaotic and messed up, with everything misplaced and gone wrong looks orderly, meaningful and beautiful; There is a sense of purpose to everything around. Each life form and living system is undertaking its own 'Hero's Journey'. A sense of wonder and anticipation! The seeds of humility and surrender begin to sprout. IsvarapraNidhAna. I am but a speck in a larger journey that I cannot yet comprehend. I begin to experience 'Inter-being' and 'Oneness'.

... at the collective level, by collectively imagining newer possibilities and co-creating newer ways of organising life in form: new forms, structures and processes of community, economy, governance, education, celebration, expression (The Arts), justice, etc. based on trust, dialogue and collaboration. An experience of Abundance unfolds as I go deeper into this work; Abundance of all things good: Resources. Connections. Positivity. Hope. Energy. New Possibilities. Ideas. Sacred Activism!

The Map: Knowledge of 'Existential Universes' - this understanding uses the intellect: To understand without arrogance or the need to control; Right use of knowledge; The Sacred Masculine. The Path: The Map might show what is where. I still need to use my intuition to feel my way through the terrains, and decide on the best path (there might me multiple paths connecting two points); Intelligence; The Sacred Feminine. **** All of the above reinforce and provide feedback to each other. Photo: Courtesy Tess Joseph "Whatever is here is found elsewhere. But whatever is not here is nowhere else." - Mahabharata.

I am just emerging out of a total immersion in the Mahabharata. My team and I offered a lab based on the purANa (pura means ancient, navam means nascent-purANa means ancient yet new). I am utterly amazed by the profound and timeless insights into human nature that the Mahabharata contains. I am sharing a glimpse of the process through this blog. The lab was embellished with dialogues: Jyothsna an accomplished dancer explored draupadi, Shashikant Achhary showed us his film "Kelai Draupadi" and discussed the research and his transformation through the filming process, we had a 5 hr performance of the traditional Koothu too. Jyothsna shared this quote with us after her dialogue: Madam Blavatsky says in the Secret Doctrine, “…All this is very puzzling, to one who is unable to read and understand the Purana-s, except in their dead letter sense. Yet this sense, if once mastered, will turn out to be the secure casket which holds the keys to the secret wisdom. True, a casket so profusely ornamented that its fancy work hides and conceals entirely any spring for opening it, and thus makes the unintuitional believe it has not and cannot have any opening at all. Still the keys are there, deeply buried, yet ever present to him who searches for them”. I believe we did find the key and it lies within each of us, the fount of our intuition as we introspected and opened ourselves to each other in the lab. I am certain that each of now carries back with us the immensely rich casket; to open, to converse with and discover our truest potential whenever we wish to; we have discovered our sakhi, the friend and guru within whom we can call up whenever we need to have a contemplative conversation. The Mahabharata has every thing- stories through which we can discover our own narrative, daivic (angelic) archetypes through which we can sense our own heroic potentials, asuric (demonic) archetypes through which we can look into our abyss; psychodramas through which we can explore our dilemmas; and in the midst of all this the Bhagavad Gita through which we explore a meditative location to anchor ourselves in and do our own samudra mantan(inner churning). Ones life plays itself out on the visible and tangible field; there are three forces that create the field: ones kartavyyam (the gifts one is born with- ones physical form), ones dharma (ones level of existence- the chakra patterns of thought feeling and action, that determines ones psychological form) and dandam (the socio-cultural context in which one lives). A profound sense of being, ones ‘self’ is energized by mukti- the deep intent of ones being to grow and evolve and to finally act from ekagrata (one pointed mind). The ideal that all of us yearn for is a situation where one can unfold with all of ones gifts, enliven oneself and ones world as we unfold, and the socio-cultural context nurtures this process. What we experience however, are situations that some times give space to a beautiful unfolding, but at other times block, distort or oppress this unfolding process. An impression of the beautiful tree we were meant to be lies dormant in the subtlest recesses of our minds, we hear the whispers of this form in our dreams and in our moments of solitude and silence. But we live our distorted selves, and experience Dukha: sorrow at the psychic level, angst at the existential level and disease at the bodily level. We then seek ways to understand the Dukha, and end it. The Mahabharata Immersion is a laboratory learning space where we use the frame works and lenses of the purANa and engage in a sakala (with all ones faculties) -sahrudaya (with a resonance of hearts) -samvAdam (dialogue). Through a duryOdhana we learn how misplaced love nurtures monstrous archetypes and gives them space to manifest; through karNa we learn how a false compensation of deep deprivation, denial and discrimination leads to a commitment to adharma; through yudhishitira we discover our deep ambivalence towards structures. For every one of our daivic potential and everyasuric potential there is an invitation to explore, there is a mirror through which to own up and examine, a psychodrama through which to play out. As we dialogue, share, explore and offer our compassionate listening to each other and offer our honest confrontation to each other, we discover our authentic self, our masks, our resistances and our shadows. We finally come to the threshold where we can cast aside the old and explore the nascent and the creative energies within. Our prANa can abandon old dysfunctional patterns, our psyche can perceive the ‘here and now’ and we can participate in Creation. We can also watch with horror how at the threshold the psyche wounded by denial, deprivation and discrimination (wounds caused by the pleasurable and the painful) shout and scream for retribution and revenge. The raw energy of the wounds say that that they would rather destroy every thing around at all levels of being and existence unless they are given their due confronts the power of Truth, Beauty and Love. We have a choice to make, at that point of existential dharma sankata we can listen to the voice of Krishna and discover total vulnerability, we can surrender all the conditioned forms of the past (however desirable or disgusting) or, we can choose to be deaf. The cacophony of the narcissistic wounds holds us hostage to our particular idea of heaven, our specific idea of the path out of our hell. The dance and the song of krishNa is everlasting, it does not need us to hear it nor perceive it, we need to discover how to open ourselves to it. In the meanwhile, endless forms of being will take birth and engage in their own drama of search and struggle; in their own striving to discover Love, in their own mad destruction of self and the other. It matters not to krishNa who abides in an inexhaustible silent, compassionate awareness and waits endlessly. Photo: the sacred space in a village where the koothu performance is held- courtesy J. Shankar If we apply an Ayurvedic framework to understanding dhyAna, what would it look like?

To explore this question, we first examine a basic idea from Ayurveda: shamanam, shOdhanam, and ArOgyam.

The next step would involve the practice of Asana that strengthens the muscles. While this is some thing unique to each person, stretching the hamstrings and working the abdominals is a must. The person also has to practice prANAyAmato experience deep relaxation. This will also orient the person to self-reflection. The total rooting out of the causes for back pain can happen only through a careful observation by the person of his/her psychological and emotional propensities. This leads to insights into how one relates to others, discovering how anxiety gets triggered, and so on. Lifestyle changes as well as deep inner transformation are called for. Now, let us look at japa (chanting) through the same lens. At the shamanamlevel, Herbert Bensons observations that we find in the book “Relaxation Response” are valid. One does not have to chant “OM”, one can chant “Cocoa Cola” regularly and the indicators of stress like pulse rate, blood pressure etc., will get lowered. However, when one chooses to chant “Cocoa Cola” there is no scope for any deeper practice, like the person who walked away after learning the initialAsana practice, one is satisfied with shamanam. The Yoga Sutra recommends the chanting of OM as a practice arising from a mind that is anchored in the Self. To start with, ones chanting will probably be mechanical. At the next stage, as ones body relaxes and the mind becomes quiet, it becomes easy to visualise a Transcendent Being. One is entering a stage ofbhAvana- ‘holding a mental form’. Chanting shloka is recommended at this stage. These shloka are often names of the Divine put in a poetic form. Understanding the meaning of the words and ‘visualising’ the form/ qualities helps one turn inward, ones subtle potentials are awakened. This then opens up the possibility of experiencing a transcendent state for brief moments. These flashes can be recalled and one can then direct ones attention to this state of mind and make it a stable anchorage. This is called dhAraNA. This is the last volitional step. DhyAnahappens when one stays with dhAraNa, it is a natural flow of the mind that is anchored in deep attentiveness, this mind then becomes even more subtle and profound through the chanting of OM. Chanting from this state of mind is obviously very different from the “relaxation response” state of mind. It can now resonate with and truly reflect the Transcendent Being. This state is calledsamAdhi. Mindfulness as it is often taught is similar to step one and probably approaches step two. This induces parasympathetic dominance in ones autonomic nervous system and all it’s attendant benefits accrue to the practitioner. A person who walks the Yogic path probably starts from the same place, but comes to the practice with the intention of completing the journey. The Yoga Sutra starts by saying “Yoga is the attainment of a mind capable of comprehending the Transcendent Being” (YS 1.2). The motivation for the practice is to be able to perceive the ‘Being’ directly, therefore, one can expect that the person will walk the path with renewed faith when the initial benefits are experienced and explore further. He/she will be prepared to take on the disciplines of the path more seriously. We see this process illustrated in the bhruguvalli chapter of chAndOgyaUpanishad: The son bhrugu asks the father a simple question “what enables life on earth? What is bhrahman?” the father vAruNi says; “brahman is discovered through intense inner search (tapas)”. bhrugu returns when through his tapas he discovers an answer to his question and says; “matter is brahman”, the father says “yes”. The son is not satisfied, he senses a lacuna in his discovery and approaches the father again, and is asked to enquire some more. bhrugu stops questioning when he touches an ecstatic level of being (Anandam) within himself. The father then reiterates the importance of matter! Let us contrast this with a person whose motivation is personal success. For such a person the Mindfulness practice is sufficient. In fact, trying to attract the person to a more inward search will be counterproductive! The initial benefits that are experienced will reinforce the belief in the practice within the utilitarian mind-set the rigours of the discipline called for will seem oppressive. Asking fundamental questions about the meaning of life, the impact one has on the earth and so on will seem totally unnecessary. What are these disciplines (tapas) that aid the enquiry that bhrugu took up? They have to do with the way one relates to the world. To illustrate, one of the disciplines is to be measured against what one takes from the world. The exchange has to be fair, one is encouraged to err on the side of generosity, but be frugal in taking. The practitioner (may we now call this person a sAdhaka, a person on a quest?) demonstrates care and concern for the well being of the world. He/she acts with an attitude of seva. A related discipline is to cultivate a sense of gratitude for what one receives/ possesses. This inner practice enables the spontaneous expression of generosity. It is important to realise that attentiveness to the inner pulls and pushes that one will experience when practicing the discipline, namely, indulging in the self on the one hand or starving the self on the other hand are themselves objects for dhAraNa and dhyAna. Such enquiry leads to understanding the nature and structures of ones mind, a necessary step on the inner path. The conversation with the cab driver that I quoted in my earlier blog was peppered with statements from tirukkural (aphorisms on life in Tamil), traditional folk songs and statements from his guru. He followed a simple food regimen, nothing spicy before starting work, no coffee in working time. “Coffee makes me very tense sir!” he said. He ate home cooked food as far as possible. “I am content with my work and what I earn, I always give free service to people going to hospital, especially for child birth. My guru told me to give dAnam.” He also told me that running a taxi is doing seva for people, he never over charges even in emergency situations. His world-view was simple but wise; he was trusting and generous and took me by surprise when he told me that he practiced Asana and prANAyAma every day. The Yoga Sutra has described many possible practices to choose from, and says; “choose a path with a heart”. I have described 7 of them in a series of blogs that I shared some time back. Our friend the cab driver practices a few of them likemaitri! I have also related these practices to the chakra and to the pragmatics of living and to working in an organization. (https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/seven-practices-manager-yogi-introduction-raghu-ananthanarayanan?trk=pulse_spock-articles) IMHO, dhyAna is essential for reversing the wounds mother earth has sustained from the relentless assault human beings have mounted on her. (photograph by the author) |

Raghu's BlogMy work revolves around helping individuals, groups and organizations discover their Dhamma, and become “the best they can be”. This aligns with my own personal saadhana. I have restated this question for my self as follows: “how can I be in touch with the well spring of my love for the world and my love for my self simultaneously” Archives

October 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed